Slavery has played a role in many societies and periods throughout history and still exists today. Not My Soul explores stories of slavery, law and freedom in antiquity and in Suriname. What influence did Roman law have on the way slavery was later organized in Suriname? How did enslaved people live in both periods, and how did they seek freedom?

In partnership with the National Slavery Museum, the Allard Pierson sheds new light on objects from its archaeological and Surinamica collections. These are objects whose stories have often been told from the perspective of those in power: emperors, plantation owners, and colonial rulers. Those are stories about wealth, power and domination. Behind this lies a reality of dehumanization, exploitation, and forced labour endured by countless enslaved people.

This exhibition places their stories at the centre. They were people whose freedom was taken from them but who, despite everything, retained their humanity through their work, creativity, care, language, love and resistance.

Not My Soul invites you to look at this past anew – to listen to it and to give it meaning.

Slavery in antiquity

Many of the archaeological objects on display were produced by, or with the labour of, enslaved people. The marble for statues and the metal for coins were cut and extracted by enslaved miners. Earthenware pots, cups and plates were made in workshops where the workforce largely consisted of enslaved people. These services and crafts required training, knowledge and skill. For example, in Roman times enslaved practitioners often worked as physicians, and enslaved artisans made medical instruments and copied books by hand. The exhibition shows how slavery functioned in antiquity, including through papyrus fragments, such as a document recording the ‘transaction’ of the 22-year-old Alexandra, who was sold for the second time.

Slavery in Suriname

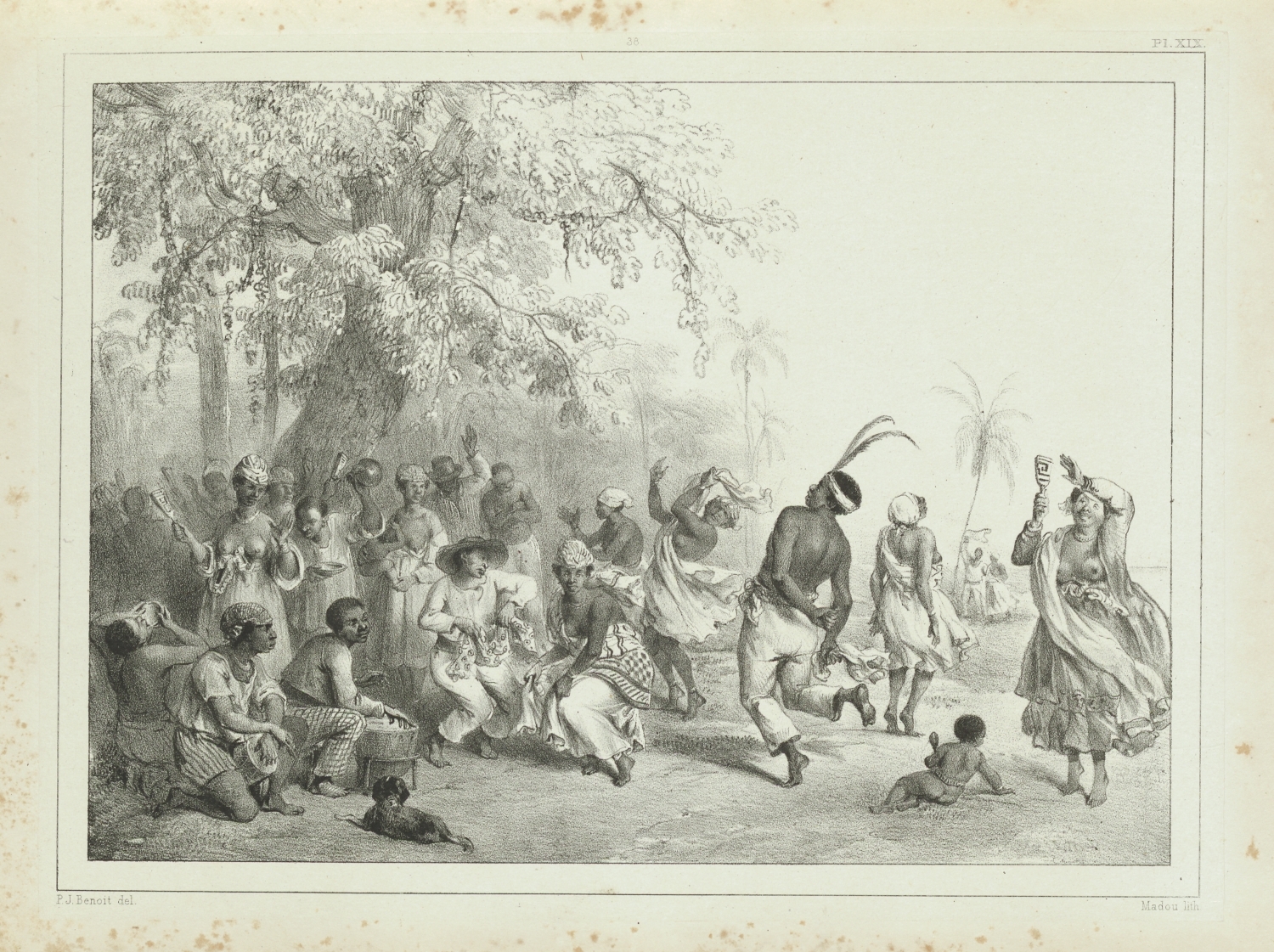

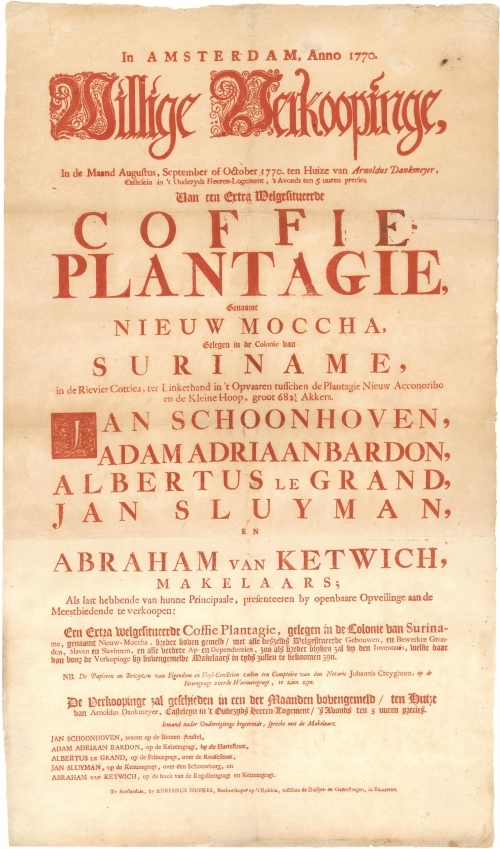

Objects from the Surinamica collection present slavery in Suriname mainly through the perspectives of colonial administrators, cartographers and researchers. On view are travel reports and letters of manumission, as well as books of proclamations used to announce local ordinances and laws. The exhibition shows that aspects of colonial slave legislation drew, at least in part, on Roman-law concepts. While slavery has not always been defined by ethnicity across history, during transatlantic slavery skin colour became decisive. Blackness was associated with the deprivation of rights and subjugation, while whiteness was equated with freedom and citizenship. Various items highlight how enslaved people in Suriname pursued some form of freedom. Dictionaries and recorded dialogues, for example, reveal efforts by white authorities to regulate language and custom, even as enslaved people developed their own. Materials also document new forms of kinship. As in parts of antiquity, marriage and forms of family were forbidden.

Contemporary art

Contemporary art plays an important role in the exhibition. Fugitives (2024) by Kathryn Smith and Pearl Mamathuba, for example, reconstructs the identities of enslaved people using nineteenth-century newspaper descriptions and notices published to pursue runaways. Now they look intently at the visitors as strong individuals. Works by Sarojini Lewis and Liara Barussi are also on view. René Tavares’s Making Memories in front of Memories (2023), from the Schulting Art Collection, depicts a Black family posing before a painting of a cotton plantation: the backdrop evokes the colonial past, but the family does not look back. The work invites reflection on how the past persists, and how new generations negotiate its legacy with strength and dignity.

Daarnaast zijn er interviews te zien met nazaten van slaafgemaakten, wetenschappers en kunstenaars. De voorwerpen uit de collecties van het Allard Pierson zijn aangevuld met bruiklenen van onder meer het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden.

Not My Soul: over slavernij, wet en vrijheid zal na afloop van de tentoonstelling op andere locaties, waaronder Suriname en het Caribisch gebied, worden gepresenteerd. Het onderzoek voor de tentoonstelling dient ook als voorbereiding op wijzigingen in de vaste presentatie van het Allard Pierson en voor het Nationaal Slavernijmuseum.