Between about 1350 and 1800, alchemy—the precursor to chemistry—was quite a common practice in Europe. Alchemy is famous for its colourful and beautiful illustrations, yet my main interest is the development of abstract symbols, called ‘characters.’ The Allard Pierson has a wonderful collection of alchemical texts in the state-owned part of the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica (BPH) collection, and as Friends of the Allard Pierson fellow I had the privilege to be in Amsterdam for two months to see what the manuscripts could tell me about these characters. To find them, I had to simply look through a great number of manuscripts in a large sweep, leafing through every page. I never knew what I was going to find and was continually surprised at the ways in which characters were written and used, the purposes that they served, and how they developed and changed.

Many of the manuscripts in the BPH collection from the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries include lists of characters, and these can be very useful to understand what alchemists at that time thought about them. Each character represents a chemical substance, a piece of equipment, or (sometimes) a concept. It took a long time for alchemists to agree upon which characters should be used, so every list is different. The most regular characters are the ones used for the seven traditional planets, which represent the most important metals used in alchemy: the Sun is gold, the Moon in silver, Mercury is quicksilver, Mars is iron, Venus is copper, Jupiter is tin, and Saturn is lead. But it took time before even those characters were fixed.

Figure 1

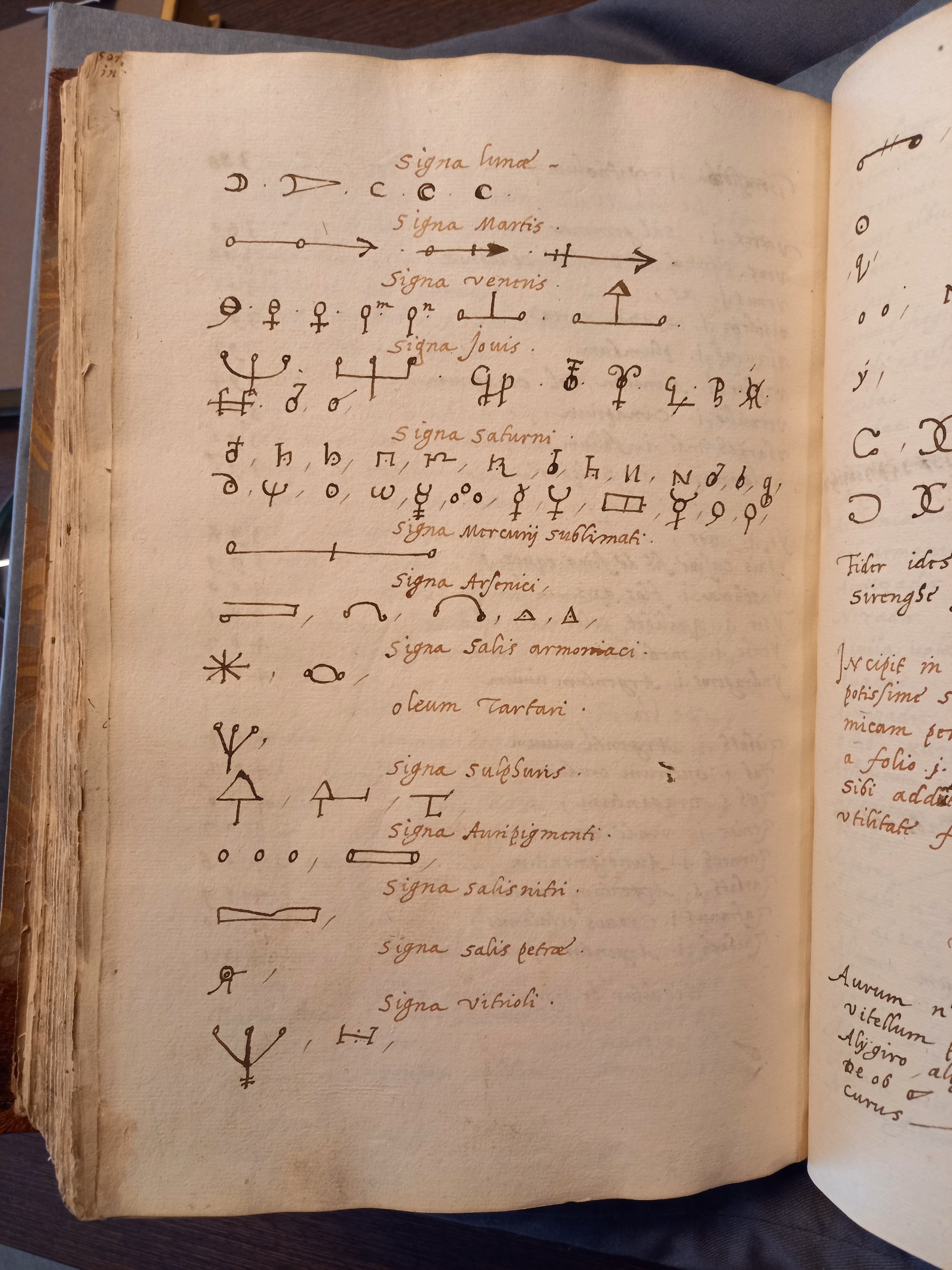

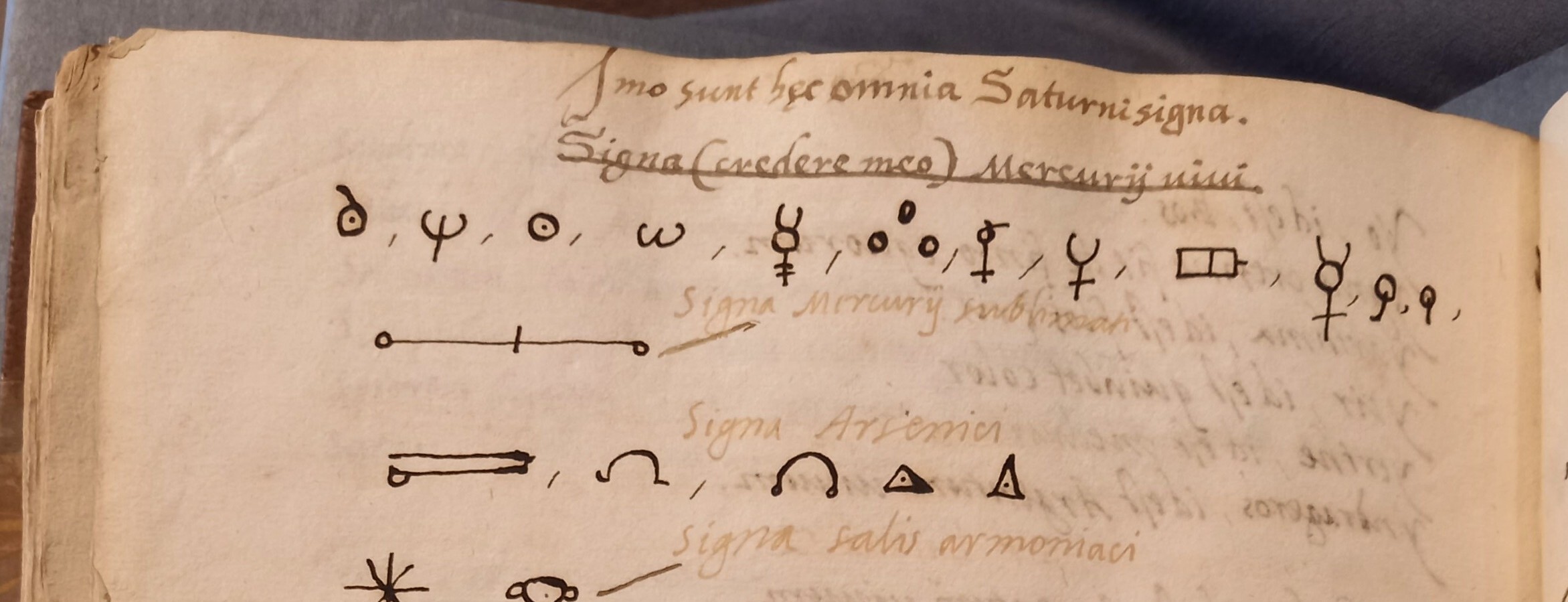

Figure 2

An early example is PH338, which is in Latin and Italian, from the mid-1500s (figure 1). There are two lists in the same manuscript, but it turns out that one list is almost an exact copy of the other. In the first list, the characters of Saturn and Mercury are put together in one group. At the very top of this second list, someone wrote: ‘these are all the signs of Saturn. Signs (believe me) of Mercury too’ (see figure 2). From this we can see that there was sometimes confusion about which characters were which.

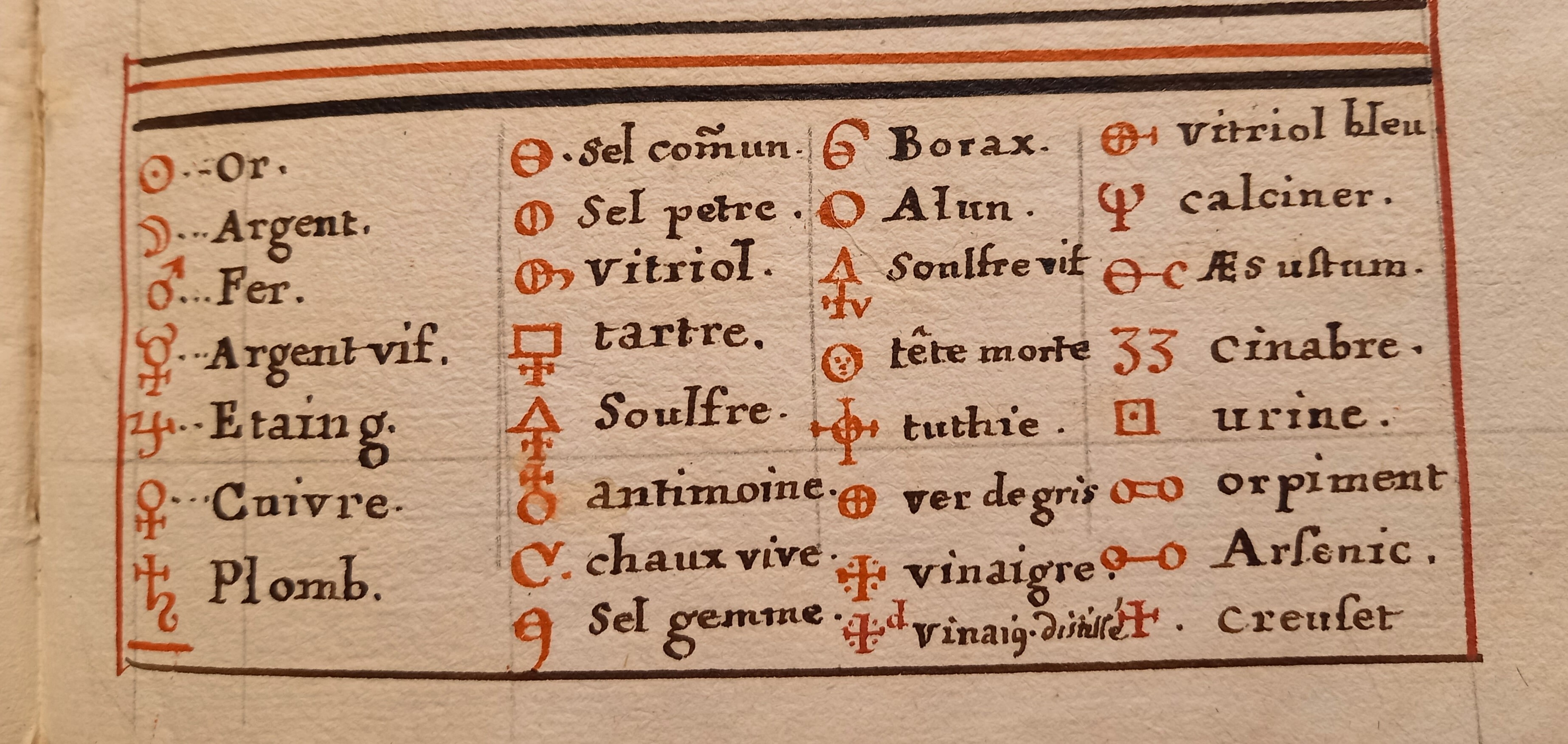

Figure 3

Once the characters for the seven metals became more regular, they are found in many manuscripts. A great example is PH185, from c. 1639 (figure 3). You can see the list of the seven metals at the very end. This list is in alphabetical order, but several letters of the alphabet are missing. Perhaps it was copied from a list which was itself already incomplete.

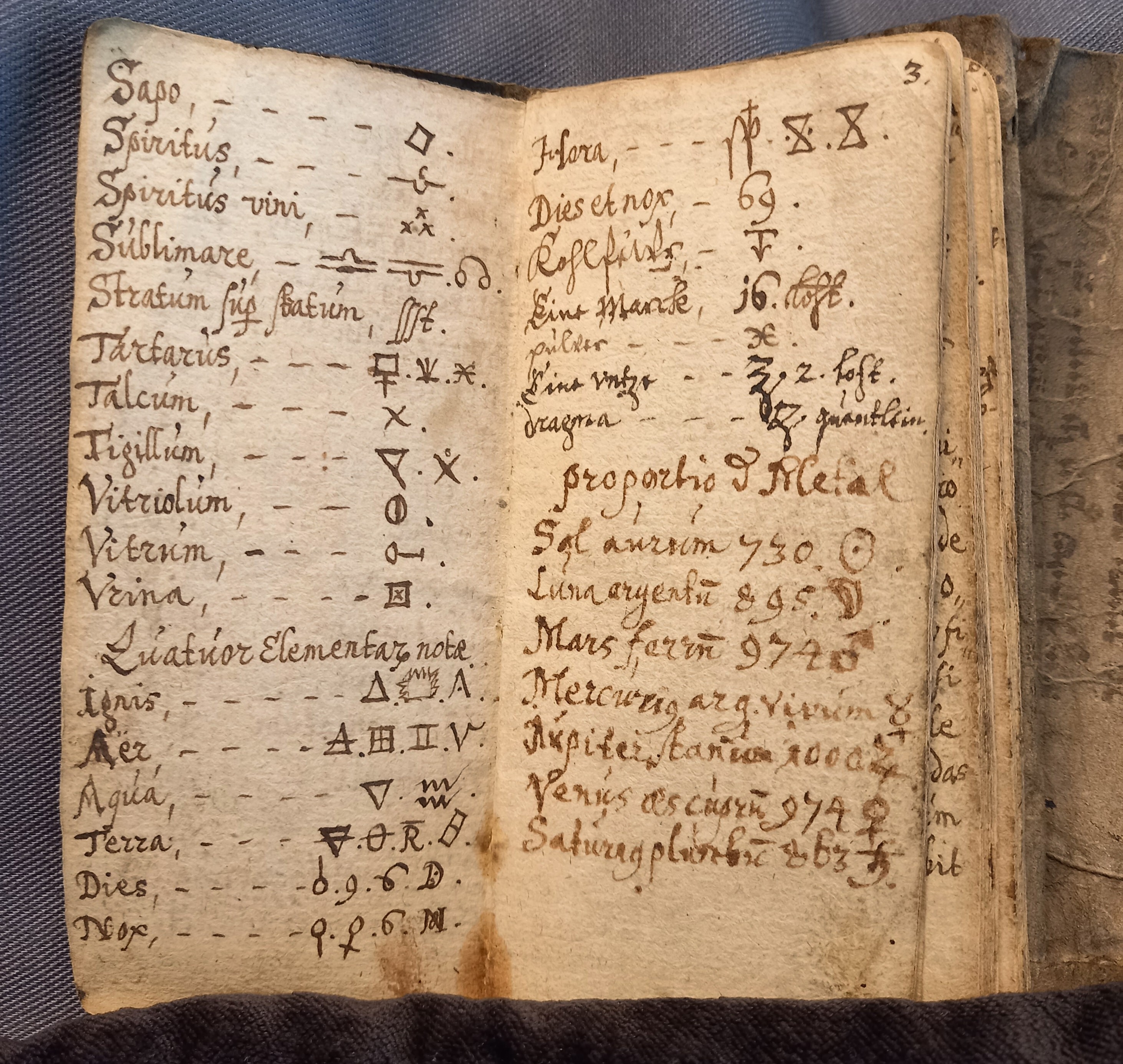

Figure 4

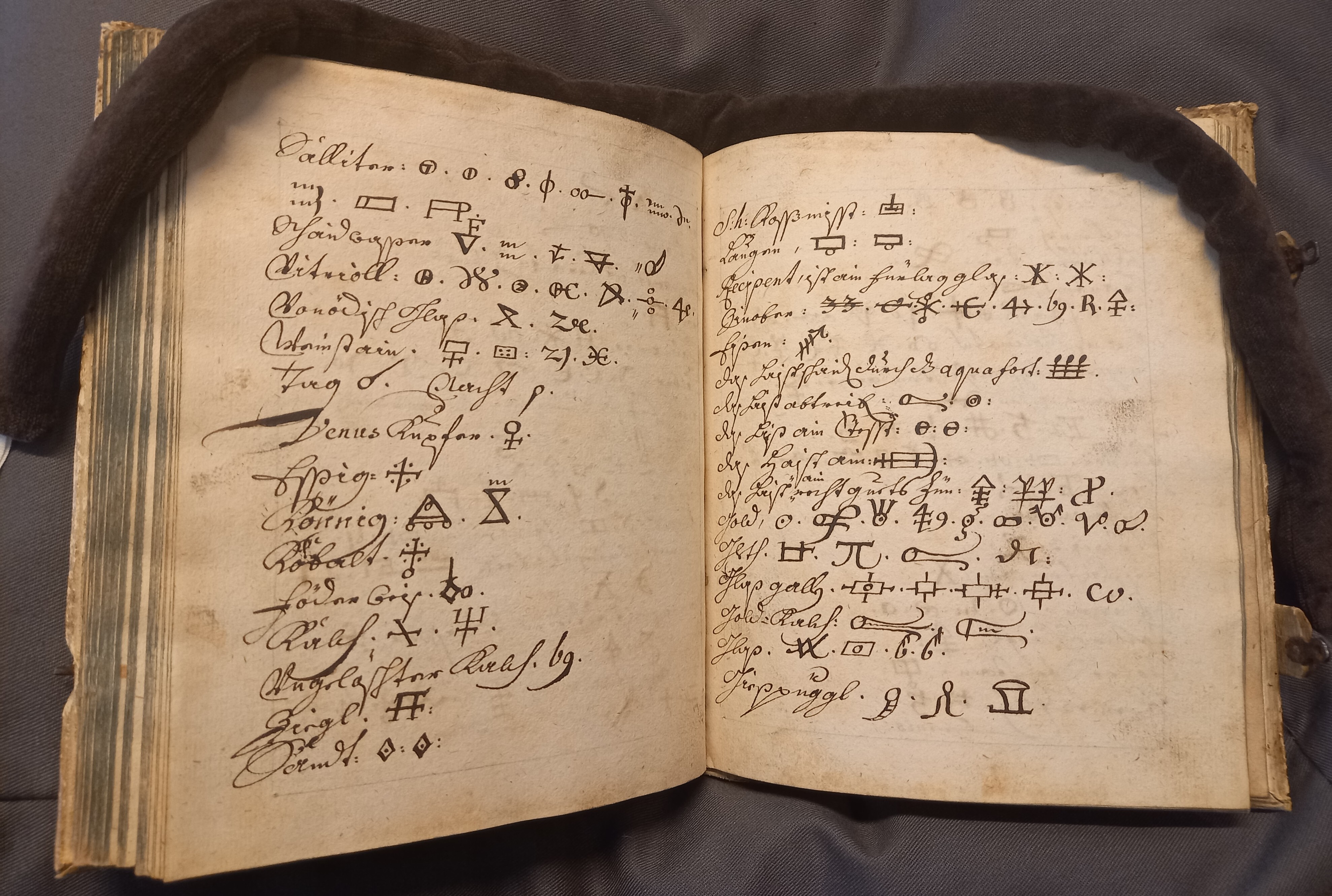

A much bigger list of characters is in PH479 (figure 4). The manuscript was copied from a printed book from 1685. However, the published version does not have a list at the end, and the scribe of the manuscript must have decided to add the list, which is six pages long. Strangely, there are hardly any characters in the main text, so the list is not helping the reader to understand the text.

Figure 5

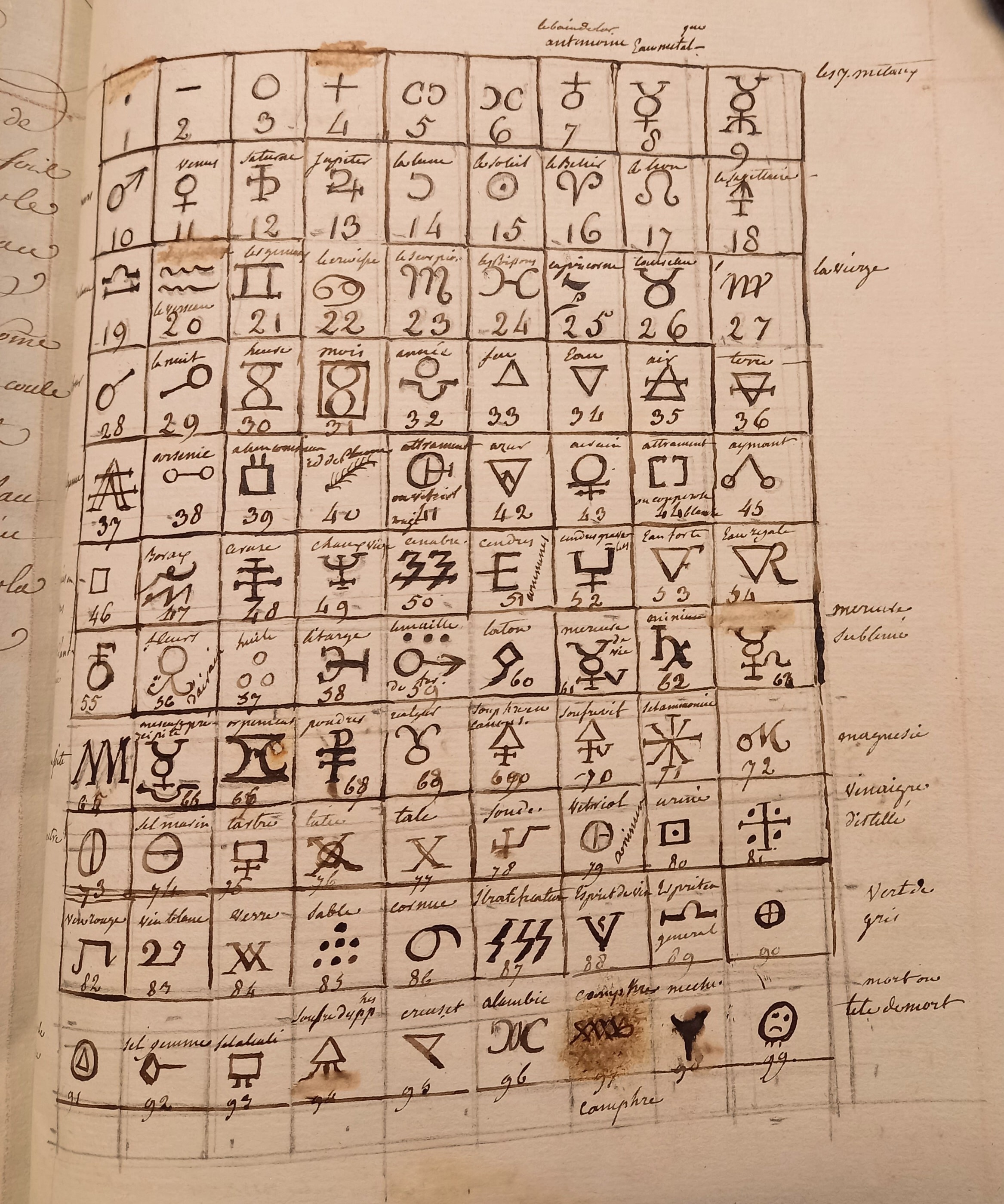

In PH324, a manuscript from 1713, the characters are arranged in a table with 99 squares instead of a straightforward list (figure 5). Each square is numbered, and the meaning of each character is given in French. This table looks like an attempt to organise information in a more systematic way.

There is a popular view that alchemy is not a real science and it is completely different from scientific chemistry. But historians of science think that alchemy should be considered an early science, and that the difference between alchemy and early chemistry is not clearcut. My thesis is that the use of symbols in chemistry has its roots in alchemical characters. Charting their development is watching the science of chemistry evolve.

Ellen Hausner

Ellen Hausner is a doctoral student in the Department of History of Science, Medicine, and Technology at the University of Oxford. Her doctoral research explores the function and significance of characters within alchemical manuscripts in the late medieval and early modern periods. In the autumn of 2025, she took up an Allard Pierson Friends fellowship in Amsterdam, followed by a Brill fellowship at the University of Leiden. Ellen was awarded the 2023 Jane Willis Kirkaldy Senior Prize, which recognises outstanding essays in the history of science, medicine, and technology, for her essay ‘Prima Materia Lapidis: A Late Medieval Alchemical Scroll and its Early Modern Reception’.