One of my favourite places in Amsterdam is a short and narrow alley called the Dirk van Hasseltsteeg (formerly the Dirk van Assensteeg) that runs between the Nieuwendijk and Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal. It is a relatively quiet and nondescript thoroughfare today with very little foot traffic. [foto 2] But in middle part of the 17th century this alley was identified by the leaders of Amsterdam’s Reformed churches as a notorious hub of dangerous activity. The source of their concern was a bookshop called In het Martelaersboek (In the Book of Martyrs) that was owned by the Mennonite/Doopsgezinde publisher Jan Rieuwertsz. In addition to some of the books that Rieuwertsz published and sold, the Reformed ministers and elders worried about the conversations that were taking place inside the shop. The activity they flagged as being particularly dangerous was a distinctive manner of speaking and listening to one another, a way of using one’s voice and of lending one’s ear to the voices of others. It was not so much the words themselves that were concerning. Rather, it was a sense that words were being used in such a way that the traditional bonds of religion were being undermined. As the people who participated in the conversation would have described it, words were being used “freely.” I suspect I am not alone in wishing we could peer inside Rieuwertsz’s bookshop to get a sense of what this exercise of free speaking looked like.

Image 2

Image 3

Unfortunately, the building in which the bookshop was located is no longer standing. And even if it were, any trace of the voices that once reverberated within its walls would have vanished a long time ago. But in the Allard Pierson’s Doopsgezinde Bibliotheek there is a small book that offers an important window into the exercise of free speaking that drew people to Rieuwertsz’s shop. Writing on the spine [foto 3] identifies the book as the Geloofs Belydenis (Confession of Faith) [foto 4] written by the Mennonite/Doopsgezind merchant Jarig Jelles (1619/20 – 1683). Jelles was a key member of the group that gathered in the bookshop and a close friend of the philosopher Spinoza, who also participated in the activities Rieuwertsz hosted. While Jelles’s confession opens the book and comprises the majority of its pages, it is important to recognize that the book also includes other elements such that it is better described as an expression of a collective project. Jelles’s confession is preceded by a letter he wrote to Spinoza in 1673, when he shared an earlier version of his work with the philosopher. And it is followed by a brief account of Jelles’s life written by Rieuwertsz. Added to all of this at the end of the book is a reprinting of Pieter Balling’s Het Licht Op den Kandelaar [foto 5] (The Light Upon the Candlestick), which Rieuwertsz had originally published in 1662. In his prefatory remarks to Balling’s work, Rieuwertsz explains that it was included because it was thought to complement and shed light on Jelles’s confession. It is when all of these pieces of the book are considered together that it can illuminate the activities that took place inside the bookshop. I will highlight just two interrelated aspects that have as much to do with the form of the book as its content.

Image 4

Image 5

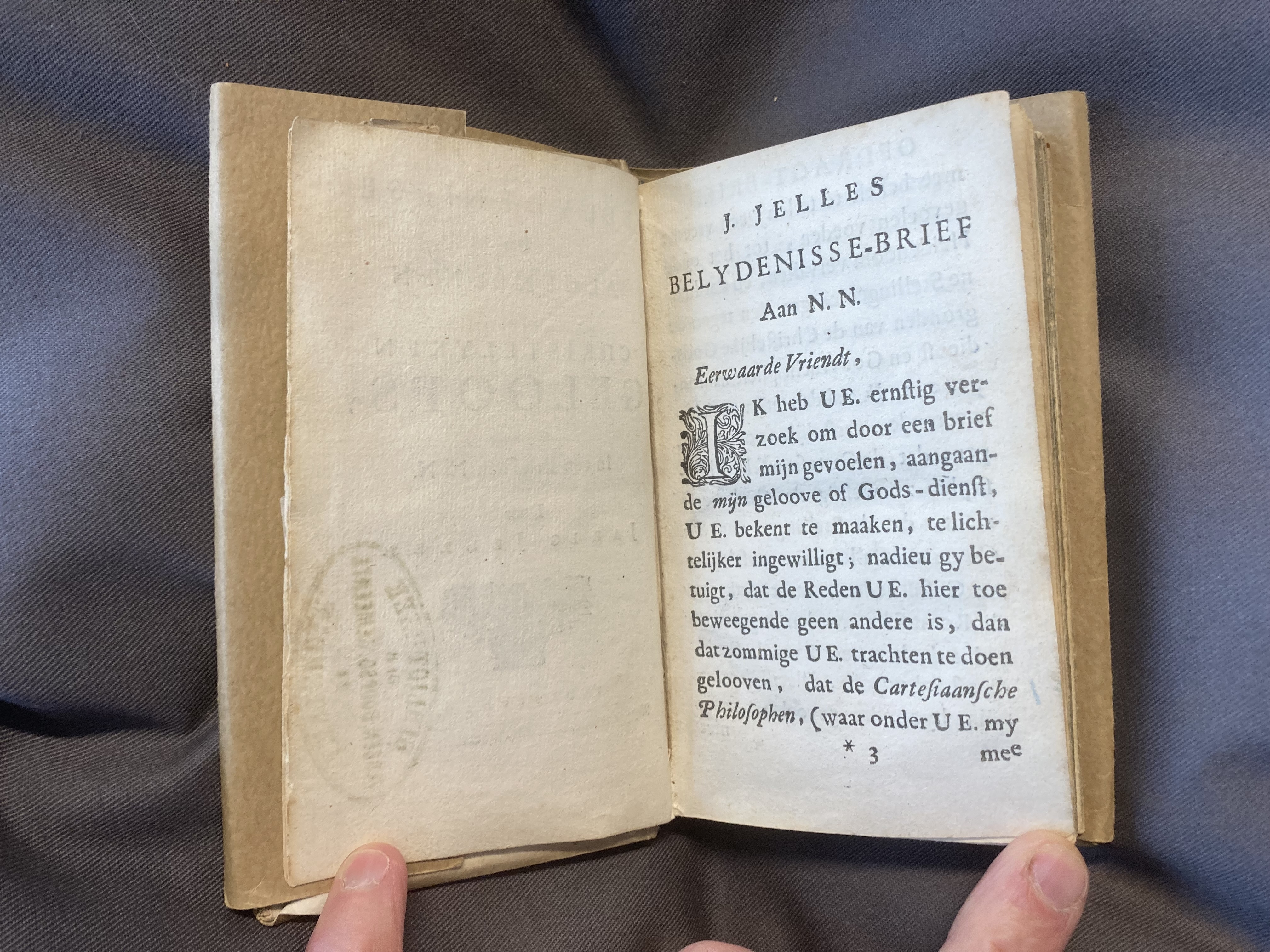

First, it is appropriate to describe this book as a work of friendship. The figure of the friend appears frequently throughout its pages and serves as a unifying thread that draws its various parts together to form a more powerful whole. In his letter to Spinoza, Jelles greets him as a “venerable friend” (Eerwaarde Vriendt). [foto 6] And he signs off by referring to himself as Spinoza’s “affectionate friend” (toegenegen Vriend). Rieuwertsz’s brief account of Jelles’s life refers to him as “our good friend” (onze goede Vriend). He also notes that shortly before he died Jelles had given the text of his confession as a gift to an additional unnamed friend who had indicated an interest in having it. It was this unnamed friend who approached Rieuwertsz about publishing the confession and suggesting that it should be combined with Balling’s Het Licht. Taken together, these remarks demonstrate that the shape of this book and indeed its very existence are due to a circle of friends who participated with one another in an extended discipline of shared conversation. This does not mean that they always spoke in one voice, or even that they were ultimately striving for agreement. But it does mean that they were engaged in a common project.

Image 6

Second, and closely related, the book takes the form of an address and in turn it invites a response. Jelles’s words are written to someone in particular and they express a desire for a reply from the person to whom they were addressed. In this way, we might say that book expresses a kind of reciprocal spirit. By publishing this confession in the form of a book, Rieuwertsz made the words of Jelles available to a much broader readership. But it is noteworthy that he emphasized the sense in which they were presented as part of a process of discernment with a friend. It was surely an option to publish the confession as a standalone piece independently of the letter which originally accompanied it. By deciding not to do so, Rieuwertsz framed the words of Jelles in a way that places the emphasis as much on how they were being used as on the specific claims they make. When words are offered in the form of an address, they do not simply convey information. They also play a part in the formation of relationships. It is significant in this regard that Balling opens his work with a lament about the way words are all too often used for the purposes of deception, defamation, and quarreling. Instead, he claims that the point of using words is to make our thoughts and, by extension, ourselves known to one another. He admits that it would be nice if we could invent a new language that would eliminate the “sea of confusion” (zee van verwarring) we often experience when we speak to one another. But because that is an impossible fantasy, he instead counsels that we should be aware of the power of words and use them with care.

Taken together, these two aspects of the book suggest that the exercise of free speaking that took place inside the bookshop of Rieuwertsz is distorted if we view it as the work of solitary individuals who sit in a position of private ownership over their words. Rather, it is part of a collaborative exercise where, among other things, words are used to bind people together in specific ways. This relational aspect of free speaking is easy to miss. We tend to associate freedom with the breaking of bonds. But that is because we tend to think of bonds applied by an external force that imposes its power upon us from the outside. The conversations out of which this little book grew were not seeking those kinds of bonds. Rather, theirs were the bonds formed through the exchange of words themselves. For anyone interested in understanding how the nature of religious discourse and forms of life were changing during the tumultuous years of the 17th century, this little book is an indispensable resource.

Bio

Chris K. Huebner is Professor of Philosophy and Theology at Canadian Mennonite University in Winnipeg, Canada. His research explores the relationship between what we claim to know and how we aspire to live, paying special attention to how the connection between these two regions turns upon what we do with words.